In September 2021 Stephen Brown and Ken Barrett gave an illustrated talk entitled Brainland: Experiments in Neuropsychiatric Opera at the annual conference of the Neuropsychiatry Faculty of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Click on the image below to see and hear that talk.

Click on the image below to see Heather Angus-Leppan Zoom interviewing Stephen Brown about the opera in December 2020 - the opera talk proper starts 17 minutes in after meandering neuro-medico's chat.

The emailed interview below took place in relation to an exhibition of concept drawings, paintings, models and dioramas that was to take place at the Library, Museum, and Archive of the Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London from November 2020 to January 2021. Andrew Lees is Professor of Neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and chairs the Archive Committee.

AL: History of neuroscience isn’t obvious opera material. What made you think otherwise?

KB: Our opera is based on three interlocking stories that I turned up whilst researching the early history of psychosurgery and the EEG, for Queen Square exhibitions. The characters were vivid, egotistical and flawed. The stories included suicide, attempted murder and conflicts of conscience. Can you get more operatic than that?

AL: Your three collaborators also have clinical backgrounds. Can you tell us about them?

KB: Stephen Brown is a composer and cellist based in Cornwall who also happens to be a retired neuropsychiatrist and academic. We worked together on musical theatre projects at medical school and maintained creative arts practices alongside our clinical work. More recently I created an animation for a song setting Steve made of a poem by Wilfrid Gibson. For the libretto we collaborated with with Andrew Platman, a retired GP turned dramatist and script writer who we also worked with at med school, and Heather Angus Leppan, a poet and neurologist at the Royal Free.

AL: I believe you have a personal connection to one of the stories.

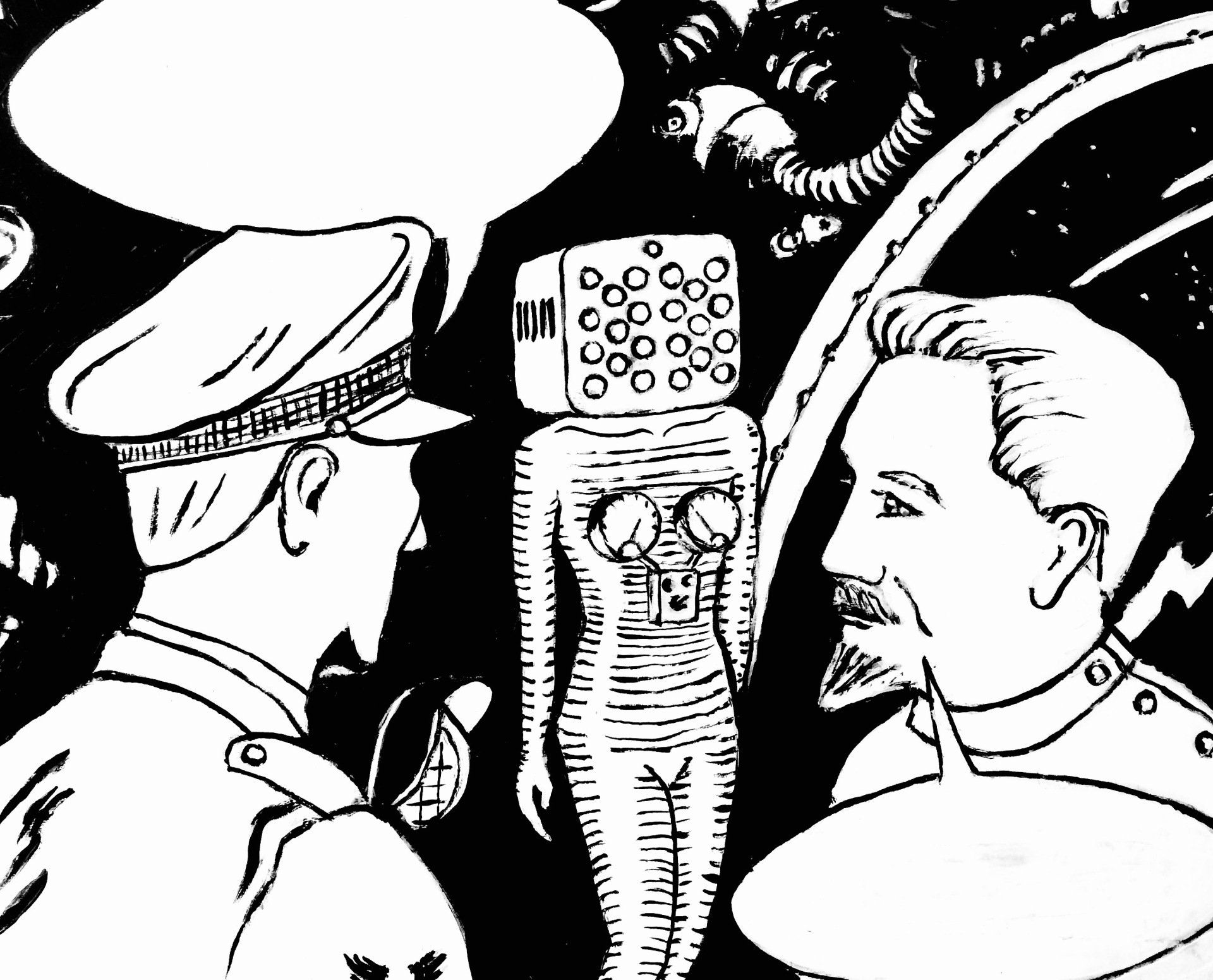

KB: One story is based around a trip to Norway in 1957 by Grey Walter, the scientific director of the Burden Neurological Institute, with three colleagues. They went to a lab in Oslo that was inserting electrodes into the brains of patients for purposes of investigation and psychosurgery. They were flown there by the US Air Force who also funded their research - fears of Soviet and Chinese brainwashing led the military to fund a lot of brain research in the 1950s, and that continues to this day actually. I came across a single photograph taken on that trip during my historical research and found I had worked closely with two of the people, 25 years later. I did painting based on it, which I guess helped the story get under my skin.

AL: How do you think your clinical and neuroscience backgrounds have influenced the project?

KB: The main characters in the opera, the protagonists, navigate ethical, risk-benefit boundaries that were all too familiar to us, but in our era thankfully we’ve had more peer review. These stories highlight the way clinicians’ and scientists’ personal ambition and ego can sometimes over-rides patient welfare.

AL: The subjects are quite technical. How did you deal with that?

KB: Grey Walter wrote a science fiction novel in the 1950s and we use a senior female character from that book as a narrator and guide. Rather than tell the three stories in sequence we interleave scenes from each, one leading into another following narrative links. In order to give the audience a window on the protagonists’ internal thoughts, doubts and conflicts we have muse character who recurs in different forms.

AL: You are primarily a visual artist. How has that fed into the project.

KB: My imagination has always been very visual so ideas for staging came up naturally during the writing process. I used drawing for designs then wax, as a sculptural modelling medium, to create models, dioramas, animations and puppets - as a way of workshopping ideas. I think my clinical career created a lot of emotional landfill and, to an extent, my art practice provides a way of digging up and recycling, processing it.

AL: Opera must be difficult to get produced at the best of times. How far have you got?

KB: Before Covid struck we had begun a collaboration with Morley College in London, and had positive meetings with music, dance and art departments. We look forward to picking that up again in 2021 and are also actively looking for other creative partners. We hope to crowd fund performances of parts of the opera that we can video to create a kind of a show reel.

Due to Covid-19 the Queen Square exhibition of designs, models and other artwork from the opera has been deferred.

The following interview with Heather Angus Leppan and Andy Platman by Jonathan Kaufman (JK), established creative director of South London’s theatre group Spontaneous Productions, took place in December 2020.

JK: Heather, you’re the only one of the four on this project who’s still working. Why did you want to get involved?

Heather: My job is very taxing so I’ve written poetry at times to help me cool off. I have loved poems since I could understand words. When Steve approached me with the opera project I seized the opportunity immediately, and it’s been wonderful to have new chums. It’s been great fun and at this particular time has proved a necessary distraction from the day job!

JK: How do you think your poetic skills come to the fore here?

Heather: A lot of the opera is very dark. I’m pretty strong on rhyme which particularly helps the lighter moments in the libretto. Maybe I add a bit of WS Gilbert to the proceedings. And four brains (as well as forebrains) are better than one.

JK: Do you see yourself doing more of this?

Heather: Absolutely yes. Brainland has really fired my enthusiasm for opera and all its astounding possibilities. I hope we succeed. I’d like to think I will have many more opportunities for this sort of work, and that this is just the start of it. I think Brainland will have babies!

JK: And Andy, you retired from general practice 6 years ago. How have you filled the time since?

Andy: Ken and I wrote a screenplay when I first retired. Since then I’ve been part of a local writing group concentrating on short plays and monologues. Ken, Steve and I go back decades, so when Ken first mooted we work together on Brainland I jumped at it.

JK: What particular skills do you think you’ve brought to the table?

Andy: Unlike Heather, I don’t rhyme. My main concern was getting the words to move the drama and trying to keep it focused. Ken and I spent quite a lot of time bouncing ideas around: I’m a little bit like the yin to his yang.

JK: What relevance do you think Brainland has in the 21st century?

Andy: I think the political aspects are fascinating. The rise of the Nazis, the military meddling in brain research, dodgy doctors. Unfortunately, aspects of this remain with us to this day. I’d like to think that by reminding us of this Brainland may, in its small way, help to keep these behaviours in check.

JK: So, what are the challenges ahead?

Andy: We’ve done this in the midst of the present meltdown affecting so many parts of the entertainment industry. I hope 2021 will give us the opportunity to start workshopping the opera so we’ll be up and running when the current emergency lifts.

A one hour programme of interviews and music extracts appeared on Radio Ensayo, Mexico on 11.3.21 Click on the poster image above to listen....